What can a Chipotle commercial tell us about the growth of classical Christian schools?

Quite a bit, I think. Read here.

Blog

What can a Chipotle commercial tell us about the growth of classical Christian schools?

Quite a bit, I think. Read here.

James Davison Hunter, LaBrosse-Levinson Distinguished Professor of Religion, Culture, and Social Theory at the University of Virginia, speaks on the moral life of children:

Wilfred McClay, a friend of classical education and professor of history at the University of Oklahoma, has an article worth your attention in The Hedgehog Review.

NY Times columnist, David Brooks, even devoted a column to McClay's article back in March.

"The sort of learning which is not in the last resort edifying is precisely for that reason unchristian. Everything that is Christian must bear some resemblance to the address which a physician makes beside the sick-bed: although it can be fully understood only by one who is versed in medicine, yet it must never be forgotten that it is pronounced beside the sick-bed. This relation of the Christian teaching to life (in contrast with a scientific aloofness from life), or this ethical side of Christianity, is essentially the edifying, and the form in which it is presented, however strict it may be, is altogether different, qualitatively different, from that sort of learning which is 'indifferent,' the lofty heroism of which is from a Christian point of view so far from being heroism that from a Christian point of view it is an inhuman sort of curiosity."

(HT: Todd Wedel)

Last April New York Times columnist David Brooks explored the differences between thick and thin institutions. For Brooks, thin institutions have a practical or horizontal orientation because members of thin institutions and the institutions themselves value one another for their instrumentality. Your local tag agency is a good example of a thin institution.

Thick institutions, on the other hand, operate more along the lines of virtue and vice and therefore have a vertical orientation. Brooks claims that thick institutions “have a set of collective rituals,” “shared tasks,” “often tell and retell a sacred origin story,” “incorporate music into daily life,” and “have an idiosyncratic local culture.” Kamp Kanakuk and the Marines are good examples of thick institutions.

Classical Christian schools should strive to be thick schools in an age when too many schools are thin. At my own school, students sing daily at matins, regularly recite Bible verses together, serve one another at lunch, and whoop with painted faces at jogathon (which pits our various houses against one another in friendly and fun competition). These thick practices are not “extras” but are central to an affection-shaping education.

Along with thick practices, my school (and many other classical Christian schools) offer students thick stories, stories that have stood the test of time. Over time, these stories develop thick imaginations. Consider these comments by one of our first graders as relayed by her teacher:

We were reading the story, Corduroy, which is a story about a stuffed bear who is waiting at the department store to be adopted by a child. The only problem is that he often gets passed by because he is missing a button and looks a little bit dirty and used. Every day, he waits for someone to notice him, love him, and take him home. One day, a little girl named Lisa sees him and buys him with her money that she had been saving up. The story ends happily with Lisa sewing on a new button for him, washing him and taking him home. After I read this story, I asked students to share a part that they liked or something that stood out to them. One student said that they liked that someone finally noticed Corduroy. Another said that they too would have adopted him because they don’t care that he had a missing button and looked dirty. Then one student said, “In this story, Lisa is like God and we are all Corduroy. God sees us when we are dirty and missing stuff and He loves us.” We then proceeded to share about how true that was and how grateful we are that God sees us, loves us, fixes our “missing buttons” and gives up something He loves (Jesus) to buy us so we can be with Him.

What is beautiful about this student’s comments is that she readily connects the story of Corduroy to the story of God’s redemptive love in Christ – the thickest of all stories (because all of creation is swept into it). May classical Christian schools orient students’ hearts and minds to the thickest of all stories, the story of God’s redemptive love found in Jesus Christ!

Eugene Peterson says:

We wake up each morning to a world we did not make. How did it get here? How did we get here? We open our eyes and see that “old bowling ball the sun” careen over the horizon. We wiggle our toes. A mocking bird takes off and improvises on themes set down by robins, vireos, and wrens, and we marvel at the intricacies. The smell of frying bacon works its way into our nostrils and we begin anticipating buttered toast, scrambled eggs, and coffee freshly brewed from our favorite Javanese beans.

There is so much here — around, above, below, inside, outside. Even with the help of poets and scientists we can account for very little of it. We notice this, then that. We start exploring the neighborhood. We try this street, and then that one. We venture across the tracks. Before long we are looking out through telescopes and down into microscopes, curious, fascinated by this endless proliferation of sheer Is-ness — color and shape and texture and sound.

After awhile we get used to it and quit noticing. We get narrowed down into something small and constricting. Somewhere along the way this exponential expansion of awareness, this wide-eyed looking around, this sheer untaught delight in what is here, reverses itself: the world contracts; we are reduced to a life of routine through which we sleepwalk.

But not for long. Something always shows up to jar us awake: a child’s question, a fox’s sleek beauty, a sharp pain, a pastor’s sermon, a fresh metaphor, an artist’s vision, a slap in the face, scent from a crushed violet. We are again awake, alert, in wonder: how did this happen? And why this? Why anything at all? Why nothing at all?

Gratitude is our spontaneous response to all this: to life. Something wells up within us: Thank you!

(from Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places, 51)

Does your school’s education foster wonder or flatten the world? Do students doze off to the texture and intricacies of creation? Do your high schoolers seem dulled by their years in your school or enlivened? Are your students filled with gratitude?

How would education look different if educators framed the educational task as an effort to develop wonder and gratitude in students?

Joseph Clair writes on St. Augustine's efforts to reform education.

Jean Twenge explains how smartphones appear to play a role in keeping teens safe, cloistered, depressed, lonely, anxious, and more likely to kill themselves than one another. Read here.

This post along with the Sasse video and Lythcott-Haims video (see below) all touch on similar themes related to how contemporary culture is impacting our children.

Along the same lines as Lythcott-Haims (see below), Senator Sasse provides robust cultural commentary on the growing number of "bubble-wrapped" Peter Pans that have difficulty leaving Neverland.

My thoughts on why developing thick schools will help combat the cynicism that too often characterizes students' attitudes toward education.

Life without God is difficult to sustain; this became apparent to me while reading Armand M. Nicholi, Jr.’s The Question of God. In this book, Nicholi pits the thinking of C. S. Lewis (the theist) against Sigmund Freud (the atheist) and the result is a fascinating interaction between these monumental minds. One of the more interesting moments in the book occurs when Nicholi brings to light some of Freud’s letters. Curiously, these letters are laced with references to God. Here are some excerpts:

“I passed my examinations with God’s help”; “if God so wills”; “the good Lord”; “until after the Resurrection”; “science seems to demand the existence of God”; “God’s judgment”; “God’s will”; “God’s grace”; “God above”; “if someday we meet above”; “in the next world”; “my secret prayer.” In a letter to Oskar Pfitser, Freud writes that Pfister was “a true servant of God” and “was in the fortunate position to lead (others) to God.”

Confused? These are certainly peculiar words coming from an atheist. Nicholi says, “Can we not dismiss all this as merely figures of speech – common in English as well as in German? Yes, if it were anyone but Freud. But Freud insisted that even a slip of the tongue had meaning.” A Freudian slip indeed.

These glaring examples point to the difficulty of maintaining a purely materialistic view of the world. After all, when one loses God, they lose themselves. In order to retain the pieces of one’s humanity, the atheist must often become a bundle of contradictions. This is how Lewis felt during his atheist days. As Nicholi reminds, Lewis, although denying the existence of God, remained angry at God for not existing. And Lewis was just as upset at this God for creating a world and thrusting humanity – against their will – upon its stage.

It would be easy to puff ourselves up over Freud’s apparent inconsistencies, but I wonder whether Christians do something similar. For Freud, there existed a discrepancy between what he publicly professed and what Freud privately expressed through his letters. Freud appears to have lived a divided life. Might Christians be tempted to do the same? While publicly claiming belief in God, could it be that many Christians live their lives without giving God much thought? In other words, is it possible that many Christians live as practical atheists?

Classical Christian education, at its best, seeks to develop students who live fully integrated lives. By filling a student’s day with worship and aiming to understand all subjects in light of Christ, we will assist students in living consistent, unified lives.

Christian education and formation, by its very nature, is difficult because it's always working against the grain of the universe. All around us, life is marked by breakdown, decay, death. Christian formation, on the other hand, is about healing, growth, and life.

How could we ever succeed in bringing about healing and life in our students? What would make us think that we could push back against the deluge of death and decay that marks our existence in a fallen world? The short answer: Jesus’ resurrection. The resurrection did not defeat death; instead victory came when Jesus stated with absolute finality, “it is finished.” In other words, death’s defeat came on Friday, not Sunday. John Stott puts it this way, “the cross was the victory won, and the resurrection the victory endorsed, proclaimed and demonstrated.”

This resurrection of Jesus will not be an isolated event. On the contrary, resurrection is the way of the future. Jesus is described as the “firstfruits” (1 Cor. 15:23), and his Church will undergo resurrection and reside in a gloriously transformed and resurrected new creation. Jesus’ resurrection completely redirected the course of western civilization, something recognized by both Christians and non-Christians alike. French Philosopher and secular humanist, Luc Ferry, attributes the unlikely move from Greek to Christian thought as a direct result of the Christian hope of resurrection. If Jesus’ resurrection changed the course of western civilization, can it change the course of a student's life? I believe it can. Christian educators in the throes of discipleship, take heart, your energies and efforts are accompanied with resurrection power (Ephesians 1.19-20)!

Joshua Gibbs explains that many schools keep sports in the proper perspective; moreover, how schools treat sports should also inform they treat the rest of the school curriculum. Read here.

Justin Bariso explains how Chipotle's use of heartfelt stories helps "woo" customers back to the eatery (after a flurry of E. Coli cases). Bariso believes these refined animations touch the heart, producing an affection not just for the story told, but also for Chipotle.

"A Love Story" is not the only video Chipotle has produced. One of my favorites is Willie Nelson's distressed voice singing Coldplay's "The Scientist":

Chipotle's use of these animations highlights the power of a well-told story. My hope is that Mindhenge videos have a similar effect, piquing interest with prospective families as well as educating and reinforcing the commitment of current families.

When schools customize the video they are communicating that the story told in the video is not simply a story they like or aspire to, but it's their story.

In one of my favorite moments of Toy Story 3, Mr. Pricklepants, a stuffed (and stuffy) porcupine asks Woody in a smug tone, “are you classically trained?” This lederhosen-wearing porcupine, while cute, has airs of superiority. I find it interesting that Mr. Pricklepants’ question seeks to learn whether Woody is classically trained, albeit of the thespian variety.

Classical Christian educators should keep in mind that it is indeed possible for classical schools and classically-trained minds to grow proud and aloof, taking themselves too seriously (like Woody’s friend, Mr. Picklepants). In order to mitigate the risk, classical Christian educators should heed the example of G.K. Chesterton, a man whose herculean intellect made its impact on the world because of his even greater imagination. Chesterton’s robust mind was coupled with a sense of playfulness and levity. This was, after all, the man who said angels fly because they take themselves lightly.

Before seeing Chesterton’s levity at work, some background is in order. During the 1950s (nearly two decades after Chesterton’s death), Dr. Alfred Kessler stumbled upon a gem. Kessler, a fan of Chesterton, found a used book in a San Francisco bookstore entitled Platitudes in the Making: Precepts and Advices for Gentryfolk by Holbrook Jackson. What made this book special is that it was a copy of the book given to Chesterton by Holbrook Jackson himself. Jackson and Chesterton, while friends, were worlds apart theologically and philosophically so the copy of Jackson’s book found by Kessler was laced with Chesterton’s witty remarks on the platitudes in Chesterton’s own handwriting. Chesterton’s handwritten comments provide a fascinating window into Chesterton’s playfulness and wit at work.

Some of my favorite Chesterton quips include the following:

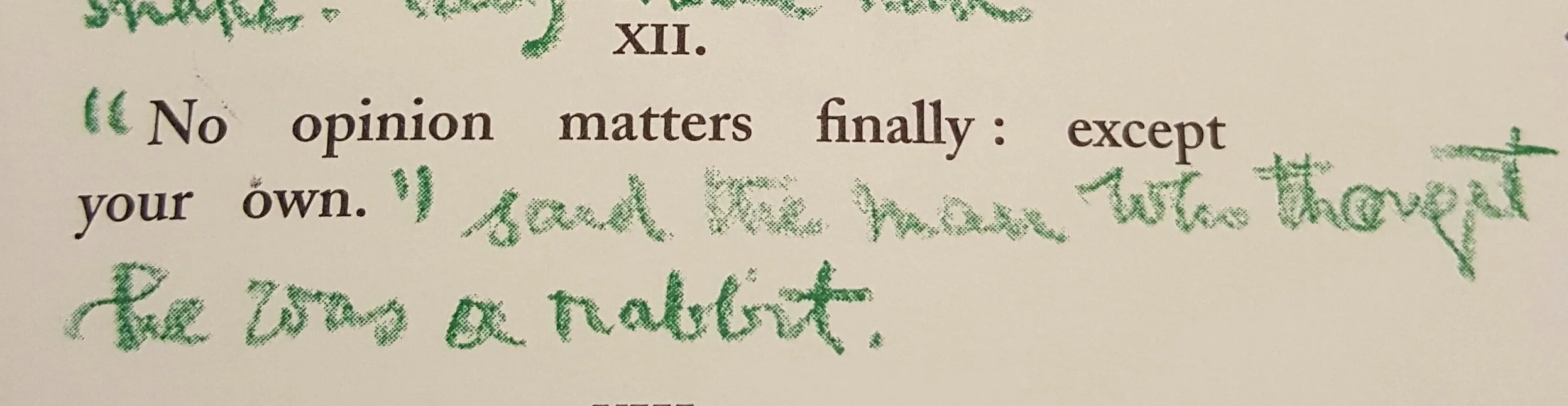

Jackson’s platitude: “No opinion matters finally: except your own.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “…said the man who thought he was a rabbit.”

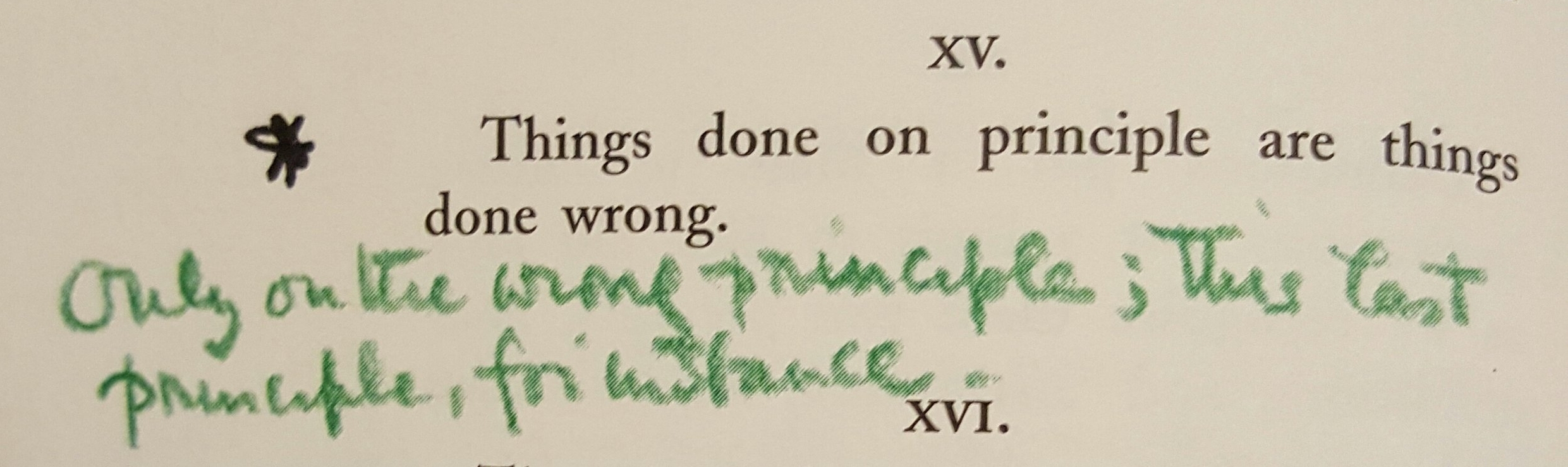

Jackson’s platitude: “Things done on principle are things done wrong.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “Only on the wrong principle. This last principle, for instance.”

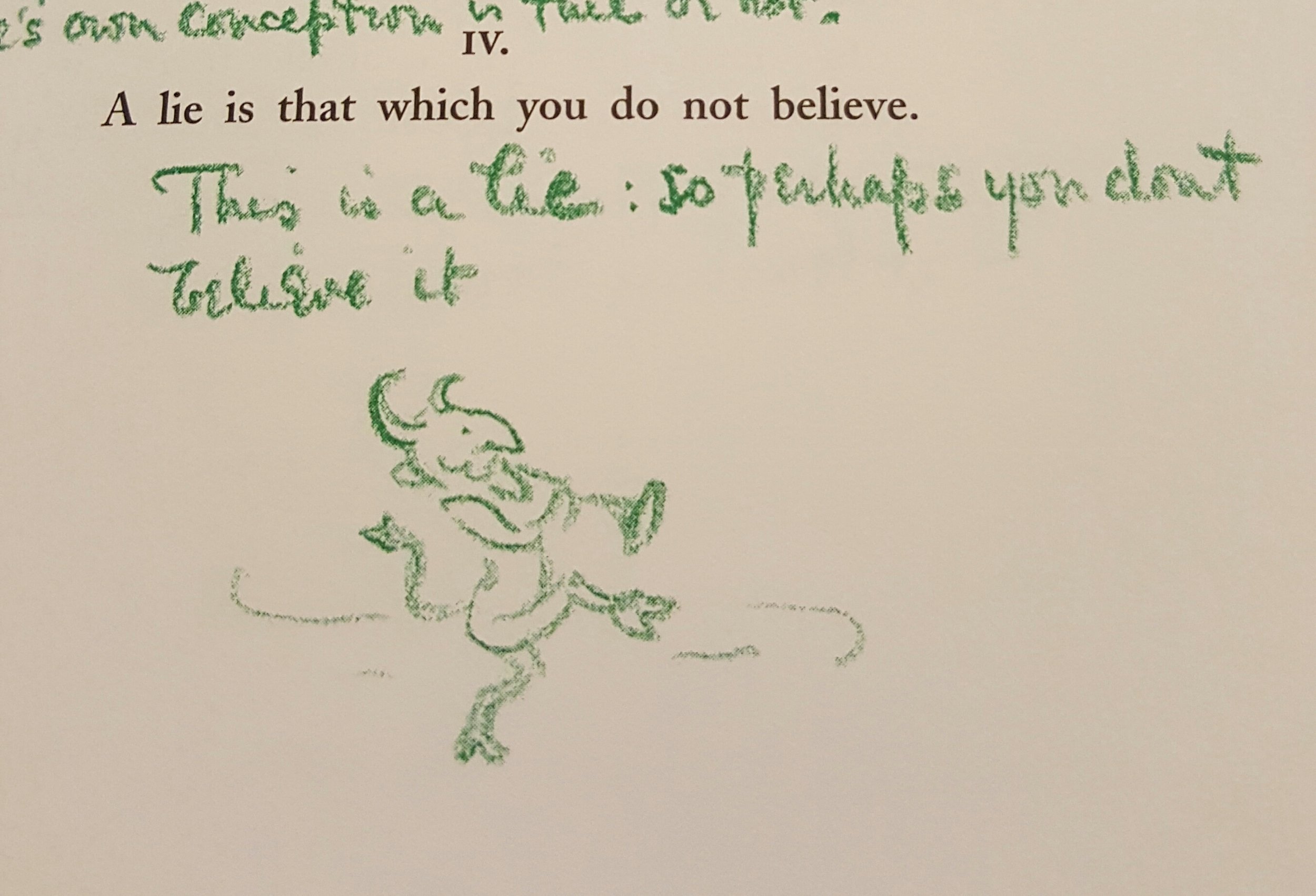

Jackson’s platitude: “A lie is that which you do not believe.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “This is a lie: so perhaps you don’t believe it”

Jackson’s platitude: “Friendship is the only respectable form of human intimacy.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “Puritan!”

Jackson’s platitude: “A man is a ship: his religion a harbour. Few men sail the high seas.”

Chesterton’s handwritten comment: “No, men do, except to find a harbour somewhere.”

Chesterton’s comments in Platitudes Undone refute Jackson’s maxims on life, but do so in a clever and playful way.

Like Chesterton, we live in an age at odds with the Christian vision of life. In such a setting, it is important that Christians cultivate the life of the mind. As Ken Myers says,

If ever there is a time when mindless Christianity is likely to produce menacing consequences, it is when the surrounding culture is embracing new conventions of thought, new institutional arrangements, new formative practices in the shape of everyday life.

Classical Christian educators would do well to cultivate the life of the mind and at the same time foster a creative, gracious, humble, and even playful spirit – a Chestertonian spirit! After all, in an age all too often marked by inflated, antagonistic discourse, the world could use more Chestertons, and fewer Mr. Pricklepantses.

Raphael's The School of Athens

University of Oklahoma Provost and classical school parent, Kyle Harper, explains why Plato's aim in education was to shape affections and not merely position students for politics and wealth. Read here.

American culture has grown increasingly hostile to boys. Recently, Allison Hull has wondered why Disney hates boys so much. But Disney's dearth of admirable male characters is part a larger problem for boys.

Christina Hoff Sommers, writing in Time, argues that school has become hostile to boys. Albert Mohler summarizes the article and considers evidence that documents a growing gap between male and female academic performance, with boys performance suffering (click here; the discussion begins at the 8:00 mark).

Classical Christian education takes seriously the differences between boys and girls, and seeks to cultivate the best of each sex. In my own involvement in classical Christian education, we spend considerable time discussing how we best serve boys in age increasingly hostile to them.

Gregory the Great Academy in PA is giving attention to what a good education for boys looks like ("boys need adventure!"):

I'm curious, how does your school create an environment well-suited to boys?

A Christian education must simultaneously look backward and forward. That is, Christian education must grapple with both the realities of the Fall (looking backward) and the realities of the New Creation (looking forward).

Without an awareness of the Fall and sin, a school's education can grow mushy, churning out students armed with sentimentality, not faithful compassion.

The schools who recognize the pinch of sin will best prepare students to "pollute the shadows," as N.D. Wilson puts it. The following video from Jonathan Edwards Classical Academy underscores the point:

But schools can't just look backwards, for students may grow crusty and cynical. In order to avoid the drift toward disillusionment, schools must look forward, to the hope of Christ's redemptive work. The Academy of Classical Christian Studies has developed a video that emphasizes the gaze forward, to the realities of the New Creation:

A balanced Christian education keeps both the Fall and redemption in view; teachers and administrators should bear in mind both Adam and Christ; students should have a keen memory of the Garden and at the same time expectant anticipation for the Garden-City, the New Jerusalem. When these bookends of Scripture frame the educational task - echoing in every class, hallway and cafeteria - students will be well-equipped to lovingly serve a world in need.

The Academy's Todd Wedel provides sharp analysis on how the educational vision of a Mindhenge video differs from a that of a video explaining the Common Core. Read the article here.